from Our Story: The Realities of Working in the Literacy and Essential Skills Field; http://www.LESWORKFORCE.ca

Part-time work, insecure employment, expectations that practitioners will put in many unpaid hours, younger practitioners leaving the field, practitioners not able to earn a living, practitioners in one type of program being paid much less for the same kind of work as practitioners in another– all issues that we were agitating about when I first entered ABE/Adult Literacy in the 80’s, and still, it seems, relevant.

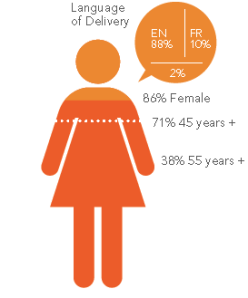

Three things crossed my desk recently that highlighted some of the same issues in the field today. First was the Literacy and Essential Skills Labour Market Study recently released by CLLN. Second was a blog post called Adult Educators: An Ageing Profession? by Ann Walker, Director for Education of the Workers’ Educational Association in Great Britain.

Third was an e-mail I received recently from Dorothee Komangapik, a literacy practitioner I first met when we worked on a national literacy research project some 20 years ago (Making Connections: Literacy and EAL Curriculum from a Feminist Perspective).

With her permission, I reproduce part of her e-mail below. I think she articulates the situation of many practitioners in the adult literacy field. What also resonates with me is her characterization of her work as an avocation more than a job.

There has been a real push to get us “old fogies” replaced by younger, more “sexy” (that’s the term that was used), more digitally connected practitioners in the literacy field. I have been indirectly urged to retire on an ongoing basis since I turned 65, more than 3 years ago. I am not ready to retire just yet.

I may not be “sexy” as a woman past a certain age, but I am a competent practitioner, digitally literate, using my electronic Smart Board daily, navigating the in-development-stage reporting system as well as cell phone, tablet, and all kinds of computers, etc. I am also quite aware how institutions operate. So far I have survived quite well and intend to remain current and relevant.

My adult learners these days are mostly immigrants (those who have worn out their welcome at ESL, many of whom had never attended school in their originating countries), those who fell through the cracks in our education system (quite a few of whom have undiagnosed learning disabilities), Ontario Disability Support Recipients (officially learning disabled), Ontario Works (welfare) recipients, and the chronic homeless. We get the occasional First Nations and Inuit learner, too, but not often.

My practice is one-on-one and I specialize in preparing low level learners to successfully challenge the tests for entering adult high school’s credit program. I also specialize in beginner literacy learners.

Younger practitioners don’t stay in the field

Over the past decade I have seen a variety of 30-something practitioners try their hand at our craft. Not one stayed. The work is only part-time — no full-time available. The learners can be lacking in social skills and therefore difficult to deal with. It’s not an easy job and requires endless patience, as you know.

Only practitioner contact with learners is paid resulting in a 4-hour paid workday being stretched to 8 or more for the practitioner to review individualized lessons and prepare individualized work for a minimum of 15 challenged learners per day. The requisite paperwork (assessments, electronic learner plans, and other non-learner contact administrative activities) also stretches the literacy practitioners’ time investment, if they are doing a good job, way beyond what younger persons are prepared submit to.

Consider also that we, as practitioners, are all highly educated with post-graduate degrees. My colleagues and I often share thoughts about our unenviable work. We are all dedicated to helping others learn, even at cost to ourselves, and we often chuckle about our apparent “co-dependencies.” It’s difficult to share with others what we do and we are aware of the overabundance of unemployed teachers. Our work is not like secure public school full time teaching jobs that include lesson prep time and result in healthy pensions at the end of a career. It’s more like part-time plus volunteer work.

When the younger aspirants realized this, they made tracks. You need an alternate source of income, in addition to the literacy, in order to live.

Literacy work as an avocation

None of this is essentially new to you, I think. It is what it has always been. Literacy is a “back-of-the-bus” issue, like homelessness, and we practitioners will always be hard put to justify spending the country’s and province’s money on such efforts whose results cannot be immediately measured in dollars.

I consider my career as an avocation, not just a way to earn money.

Of course, because I have always been an adult educator I have always been term-hired or part-time so I have not been fortunate enough to set aside money for my retirement. Therefore, being of reasonable health and of sound mind, I intend to continue my career until I am no longer able. Thank God that no one can force me to retire without scrapping the entire program. I have been administrator for a short period, so I know how regulations and laws can be manipulated to suit the institution without leaving a trace.

Thank you for allowing me to review why it is that I am taking work home and work long hours. I actually care about my learners. That is my bottom line, I guess.

For more information about Dorothee Komangapik, visit her website Uqausivut.

If there were such a field as “near-adult literacy” that would be the field I teach in. My students (teen parents) are nearly adults, and many tend to lack basic literacy skills. I’m not sure how my American counterparts in adult lit fare, but I’m guessing there are similarities. Mostly female. Mostly paid little. Mostly older. I see the same gap in public ed that Ms. Komangapik mentioned regarding older vs. younger teachers also. The younger ones don’t stay in the field long, and many don’t have the same commitment or work ethic as older teachers. The 30-somethings at my school are generally unfocused and free-form in style, which in my opinion, leads to chaotic learning environments that do not serve our population particularly well.

As someone who teaches at a public community college in British Columbia, I am dismayed to see the vast gap between my experience and that of my colleagues in non-profits: I am a member of a faculty union that advocates for decent working conditions, pay, and benefits. Others often do not have access to this kind of advocacy and strength in numbers.

I heartily wish others who do the same difficult, highly-skilled work I do could be treated as well. But unfortunately, even the “secure,” well-paid college jobs are being slowly eroded. In the college system, many full-time faculty who retire are not replaced–thus leading to the elimination of positions (without necessarily being counted as official “cuts” to programs). Or they are replaced by part-timers or contingent faculty…which leads to exactly the problems outlined in this post.

Literacy seems to be something many acknowledge is necessary, but that few governments actually want to pay for.

I bet this is a field largely dominated by women workers…always a flag for low pay and no job security or respect.

Hi Kate,

(I’ve copied this from a reply to your comment on my blog. The timing of both blogs is a telling coincidence.)

The parallels between the situations in Canada and the UK are remarkably striking.

Why is community learning so marginalised as part of the education landscape, even though adult literacy and numeracy are key elements of global education goals as well as individual nations’ plans and are central to social and economic development?

Dorothee Komangapik’s perspective is interestingly defiant. She’s right about her wisdom, experience and adaptability, but even she can’t go on for ever.

We need urgently to raise the visibility and status of working in adult and community learning and to make sure that it’s a realistic career option for people of all ages. I’ll be interested to follow progress in Canada and to learn about comparisons with other nations.

Do any of them have this cracked?